20 Aug GROAN, GROIN, AND TENDERLOIN

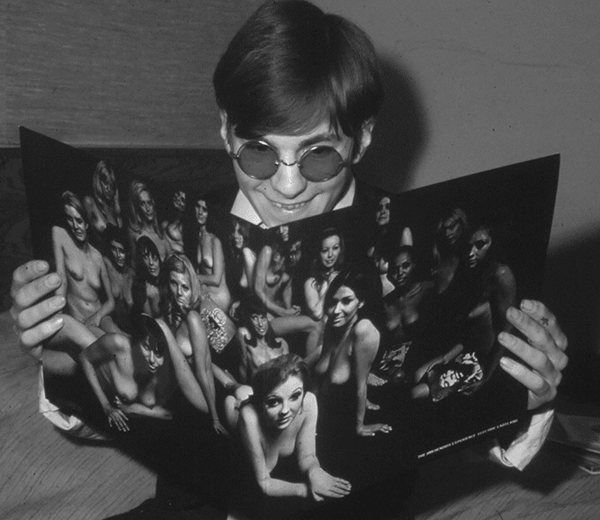

It’s become quite grotesque and tasteless, this new bizarre kick in pop. At first it was funny—the Fugs doing their lighthearted send-ups of hypocrisy, Jimi Hendrix playing his guitar like a pneumatic drill or whatever, the Beatles singing Why Don’t We Do It in the Road? but never explaining just what it was. Then it became a little more serious.

The lyrics became blatantly direct. Country Joe and the Fish opened their show with a four-letter-word locomotive cheer, which ended with the audience bellowing the forbidden word. Rumors swept the pop world that members of a prominent group had urinated in a bucket on stage. In spring ’69, Rolling Stone, the most respected U.S. pop publication, reported that a rowdy group, hitherto known mainly for deafening performances, had defecated on stage during a Seattle concert.

In Florida, the Doors’ controversial lead singer, sex symbol Jim Morrison, created headlines with a performance which resulted in police charges that he had simulated masturbation and oral copulation on stage. Morrison’s audiences usually average about 16 years of age; there was 14,000 fans on hand for that Miami performance. Morrison, said to have skipped to the Bahamas, was charged on six counts. He subsequently returned to Los Angeles and gave himself up and is now fighting extradition to Florida.

In Toronto in March, the Mothers of Invention played two concerts at the Rock Pile. The first was innocuous, but at the second show a former member of the group simulated sexual intercourse with a girl who turned out to be his wife, then for a finale turned his back and dropped his trousers. Rock Pile manager Rick Taylor, 24, didn’t like it, but he didn’t try to stop it. “Are you crazy, man? Just picture me trying to stop it in front of 2,000 fans.

“I do think it was kind of an insult to members of the audience who’d paid $3 each to see a musical group. They didn’t pay to see someone’s backside.” Taylor says, however, that he would take action if a group member attempted to masturbate on his stage. “I’d ask my stagehands to stop him, and if they refused, I’d keep on moving up the staff ladder —firing people. By that time I figure the artist would probably have finished anyway, and I wouldn’t have to stop him.”

One girl who was at the Mother’s concert disagreed. “I mean, tough luck. Who cares if a guy takes his trousers off? Plenty of worse things can happen. Big deal.” (She didn’t want her name to be mentioned in case her mother should see it.) Frank Zappa of the Mothers of Invention is equally unconcerned. “The incident was simply something unpremeditated, unexpected even by the Mothers.

The guy wasn’t even a member of the present group. And he just came on up and did it. What could we do?” Zappa is clearly not upset about onstage masturbation or defecation either. “What is there to be uptight about? Let’s face it, the people who go to the Doors’ shows expect something like that. They hope for it. TV has primed them for it.” The Mothers of Invention will return to Toronto for a Massey Hall concert.

Exactly what they intend to offer as proof of their free spirit isn’t known. Inspector John Wilson of the Toronto Morality Squad makes no bones about what police would do if a performer masturbated in public. “Regardless of where it was or what it was, we would arrest him immediately and he would be charged.’’ Since there were no police at the Mothers of Invention Rock Pile concert in February, Wilson wasn’t sure if an arrest would have been made. “It depends on what underwear he had on, and what actions and motions took place.” (In fact, he dropped his underwear too.)

It does not take a citizen’s complaint to make the Morality Squad act, and the law relating to obscenity is loosely worded. “We’re very flexible. We go by what is currently acceptable. What the people will accept is okay by us.’’

If, then public intercourse is considered acceptable-next year, a pop group may do it stage without fear of arrest? “Well, Compared to what’s happening in theatre and films, pop antics are perhaps not all that exceptional. But because they involve teenagers there is considerable concern.”

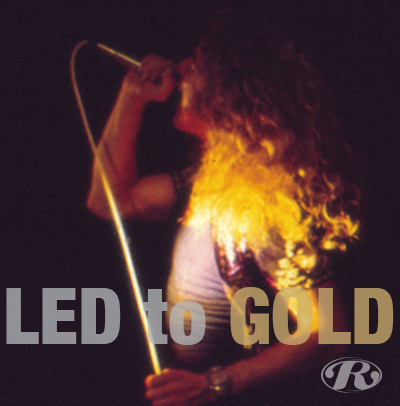

Of course, pop music has always been about sex. But so has much other music. Pop just deals with it in a more straightforward manner. The singers mightn’t have said it, and the teeny- boppers at a Beatles concert may not have understood it, but sex was always the inner motivation. When Fabian drawled, “Well, if you want me, come on and get me,’’ he wasn’t talking about dancing at a high school prom. Pop has been getting progressively more blatant and convention-defying since the pelvic pushes of Elvis Presley created such a stir in 1955. First it was the lyrics.

They suggested in that strange language of youth all sorts of things. “Make love to me” became a favored fervent phrase. But the puritan ethic kept the performers, if not the lyrics, under control. Then in 1963, out of Hamburg’s sin filled Reeperbahn, came the Beatles and the age of open sexuality began in earnest. The Rolling Stones bowled onto the scene and Mick Jagger became known as the lead singer who stuffed handkerchiefs down the front of his trousers. Jagger gripped the microphone like a monstrous phallic symbol, and then proceeded to thrust it against his own genitals.

The crowds, the majority being girls, loved it and their parents cringed in horror. Other English groups followed Jagger’s lead and one singer, P. J. Proby, had his trousers specially made so that the seams would rip apart at an appropriate moment, revealing a section of pallid English thigh. Doctors reported at the time that female pop fans actually had orgasms while watching these displays.

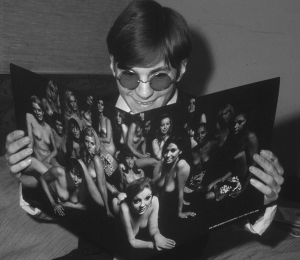

It became fashionable for entertainers to doff their shirts, or at least to leave the top four buttons unfastened, and to wear trousers so tight that even a grass-skirted South Seas Islander would have been stunned by the revealing profiles. Defying convention was as far away as the nearest four letter word. Pop groups (and subsequently teenagers generally) took to using that four letter word casually and with impunity. And a number of old hit records contained words or phrases which radio stations apparently didn’t understand (although their listeners did).

Even the groups’ names suggested profanity; for example, Vancouver’s Mother Tucker’s Yellow Duck. Jimi Hendrix took to rubbing his guitar against the microphone, producing a horrible wailing sound, something like a dozen cats on the back fence at midnight. Janis Joplin used any and all four letter words whenever possible, and wore see-through dresses, though at 150 pounds or better it was doubtful if anyone actually wanted to see through.

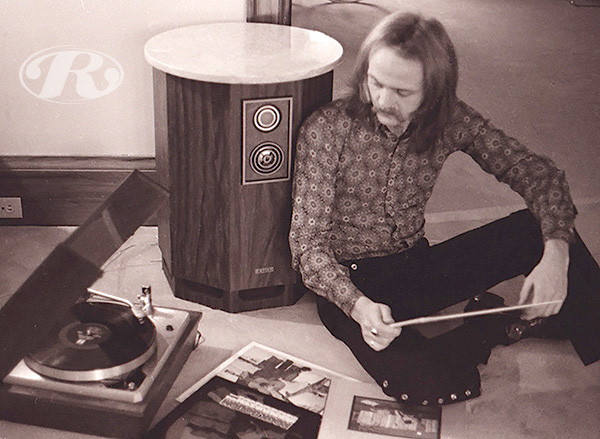

After Hendrix, the guitar became entrenched as the sex symbol of pop. The way it was played by some musicians it could have been an extension of their bodies. Hendrix moved on to kneeling on his guitar and playing it with his teeth. Some singers lay on the floor. The Doors all but exposed themselves on stage for two years before Morrison allegedly finally ended the suspense.

His act was so blatantly designed to frizzle the young teeny-bopper’s heart that it was a pity to see the look of frustration on their sweet young faces at the end of a concert. In retrospect, it seems obvious that pop was slowly moving toward public masturbation; sooner or later it had to happen. Pop music, even in Sinatra’s day, was geared to raising the sexual urges of audiences to near hysteria level, and then leave them hopelessly unsatisfied.

Thus the only course left open to these frustrated souls was masturbation. But this does not really explain why some performers may have masturbated, urinated and defecated on the stage itself. Is it just a matter of kids giving the Establishment yet another kick in the teeth? Or, are the performers unbalanced? What is likely to happen next, and how long will it be before the Establishment cracks down? In short, how much longer will the average parent allow his children to attend pop concerts without fear for their basic decency.

Toronto psychiatrist Dr. Daniel Cappon finds the situation quite predictable. He believes that pop audiences will, inevitably, witness sexual intercourse on stage before performers return to more restrained behavior. Frank Zappa agrees: “It’s a logical form of entertainment for the frustrated white public. I mean, how long can this era of gunslingers shooting up each other and all that violence—which is only a substitute for healthy sexual activity—how long can all that go on?’’

Recent public performances are not, Cappon insists, the acts of “a group of perverts playing guitars.” He thinks the motivation for such actions is much more deeply rooted and is allied with youthful adventure in other fields. “The big danger is to try to explain it away too easily. You’ve got to look at this from several viewpoints. First, music is, and always has been, preoccupied with love and sex. You’ll recall guitarists centuries ago serenading under the balconies of their sleeping sweethearts. And personally, I can think of nothing more seductive than the music of Debussy.

“In pop music, you have the combination of the raw, naked rhythms of the Negro, and this traditional sexual accent. The pop beat is basically more naturally sex-oriented than anything I know, intercourse included.

“Body movement, which naturally follows when listening to pop music, is the most basic form of sexuality. It begins at infancy, when you’re rocked in a cradle. It’s kinetic energy. Pop concerts,” says Cappon, “bring the underlying sexual influence of pop to the surface, and in a hurry.

“In addition to the basic sexual beat, the environment is conducive to sexual activity. You have the influence of a dark arena (compare this with the unlit bedroom situation) and a massive love relationship between the audience and the entertainer. They hang on to his every movement.”

The audience, presumably, is turned on to some form of sexual current. But what of the entertainer? “The behavior of the performer is even more predictable than that of the audience. He, like all young people, has a desperate need for originality and individuality. There is a frightening need, a real despair about being different. A few years back, it was easily done. You just had to wear an unusual cravat.

“Now, it’s damn near impossible. This despair for originality increases with the number of people in the immediate surroundings. In this society, it’s reaching panic proportions. Thus the performer resorts to shock value.” The flaming mask of Arthur Brown, the equipment smashing orgies of the Who, the effigy burning of the Move are examples. Zappa figures that groups will soon try to top Morrison’s act, and then it will become a case of keeping up with the Joneses.

Eventually, Cappon surmises, an entire group may masturbate on stage in time to the music. But while Cappon doesn’t worry about what happens on stage, he is concerned about the audience’s apathetic reaction, a passivity he attributes to a unique state of mind among the young. “We are now seeing the results of the first generation of fully passive voyeurs. These kids expect something to happen, masturbation at the very least. They’ve been watching TV for eight hours a day and they’ve seen everything: wars, immolation, assassinations, torture, almost everything except love and sex—so very little can surprise them. “But being voyeurs, they only watch. They don’t do.

“They’ll do nothing to stop whatever goes on out there on the stage. And the larger the crowd, the less likely they are to do anything. In fact, they’re conspirators—goading the entertainer, challenging him to do something outrageous.” Cappon criticises television for not doing enough to discover what effect it’s having on viewers’ minds. Young people’s especially. “Marshall McLuhan and I offered them a chance to see the direct results of what the medium does to the mind of the viewer, but they didn’t want to know about it.

“The only survey they care about is Nielsen (the audience measurement rating system). Like the computer business, they’re terrified of mass negative reaction.” Zappa, too, is sharply critical of television. “The medium has done so much harm. The people who control it are doing a great disservice to the public. How can the public be corrupted by masturbation—a natural act—when they’ve seen a completely warped view of life on TV.

Television is the most harmful thing I can think of right now. And it’s all premeditated. They do it on purpose. They deliberately distort life, present it as a two-part western with lots of killing and no sex. What sort of entertainment medium is that?” Cappon says that the middle aged, middle class masses are indifferent to vulgar acts because of their own life experiences and attendant guilt feelings. “That old line used by kids at their parents—’look what a mess you made of things’—has had its effect. The parents are aware of the mess—TV helped that awareness—and they feel responsible for it, rightly or wrongly.

They’re afraid to unleash a conservative backlash; they saw what happened in their own lifetimes through Hitler, Mussolini and the like. In any case, the day of righteous indignation about anything seems to be gone.” Cappon emphasizes the fact that while there is nothing new about sex, what is new is the trend to desexualization. “Sex is fast becoming just a very superficial form of art. You can watch it in movies, at the theatre, at pop concerts now. So the voyeurs keep watching, and not doing.

That’s the tragedy of it all. When you see somebody else doing something, why bother to do it yourself? “It will go quite a bit further yet. I think we’ll see sexual intercourse on the pop stage. But there won’t be any backlash until we start seeing deviational behavior. Then, I believe, we’ll head back to a restrictive, submerged, submissive Victorian-like society. “But it’s going to take between five and ten years for it to happen.”

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Although there was never any doubt in my mind that The Globe and Mail’s Ritchie Yorke was the most informed and interesting pop writer in Canada, I must say he has exceeded himself in the article, Groan, Groin and Tenderloin in The Globe Magazine (May 17).

It is rare to see the two subjects of pop and sex handled so maturely and with understanding. No doubt there will be many shocked readers. But the function of any newspaper is not only to entertain, but to explore and explain. This particular piece of reporting has done all three. Toronto, my sincere thanks to your establishment for the article Groan, Groin and Tenderloin. The degeneration of some facets of the pop-music industry into a base display of sexual gyrations is an issue that has worried me for some time.

Now that an authoritative voice has exposed the facts, one can only hope that this is the start. I urge you to bring to the attention of the general public the need to understand why we have reached this stage. Dr. Daniel Cappon expressed his views on where this will lead us, but is this based on a projection of human relationships as they stand in May, 1969? If so, there is a chance that the bulk of apathetic or misinformed parents will make a constructive effort to reach a higher level of communication with their children—the fuel of the pop industry.

Should this be achieved, we can hope that younger members of our society will not need to inflict these “cheap thrills” on their immaturity and confusion, but can turn once again, with respect and understanding, to their parents.

Toronto

Good grief! Someone in Toronto finally got up enough nerve and decided to tell the whole truth about the latest development in the rock scene (Groan, Groin and Tenderloin — The Globe Magazine — May 17). I am sure many people will probably be offended by the article’s contents, but no one can dispute the fact that a new age in rock is here (it has already arrived in the theatre and the cinema).

Ritchie Yorke and The Globe and Mail should be commended for recognizing what is more than a fad, intelligently analyzing the sociological implications and then daring to admit this is truly what’s happening, baby.

Toronto

I am writing to complain about the article published in The Globe Magazine on May 17, written by Ritchie Yorke and entitled Groan, Groin and Tenderloin. I, personally, was shocked. However, on talking to others, I found they thought it might do some good, as some parents are unaware of what is going on, and this article enlightens them.

The people I talked with would like a rating put in the newspapers regarding the shows, similar to those ratings shown for the moving pictures. The parents would then know whether to allow the younger teenagers to patronize them. I suggested to my children that this magazine be kept for the adults only—of course, for this issue only.

This, they agreed to do.

Islington

I protest the article Groan, Groin and Tenderloin. Man was given a divine spark that sets him above the animals and “a little lower than the angels.” To me it seems that the behavior of man as described in your article shows him debasing himself so that he becomes much lower than the animals. Surely the function of the pop groups mentioned is to entertain. Can the use of the public stage as a bathroom, or as a bed for the most intimate of relationships, be described as entertainment? Surely not. It seems to me that the press must be fully aware of its influence and should be interested in raising the standards of today’s youth. Certainly no one can benefit from the publication of such an unnecessary and disgusting story.

Hamilton

The article, Groan, Groin and Tenderloin, by Ritchie Yorke (The Globe Magazine—May 17) is a most repulsive example of lurid journalism. One would consider The Globe and Mail a publication fit to enter the average home. Is it to be required now that parents hastily snatch out the magazine section and either hide or burn it before any of the school children read it? “Pop music” is a polar term to the young; anything pertaining to it is sure to be sought by them. If Mr. Yorke, in his review, merely stated the “spectacle” was a bit of obscene vulgarity, that would have been adequate. It is an offense to good taste and judgment to go on to describe in detail actions for which domestic animals would be put out of the house.

San Jose, Calif.

I would like to congratulate those members of The Globe and Mail who were responsible for printing Ritchie Yorke’s article. The editors deserve credit for challenging a senseless taboo which would keep the word “masturbation” out of print and would keep legitimate news stories from us because they have to do with sex.

Mr. Yorke deserves congratulations because of his responsible handling of a delicate subject. I commend his article to classes on current social issues and to journalism students interested in good examples of writing style. One reason I have no hesitation in expressing myself in these terms is that I have come to think of The Globe and Mail over the years as one of the civilizing influences in this country. I just automatically expect that an article like Ritchie Yorke’s will reflect a spirit of honest concern about what is going on around us and I was not disappointed in this regard.

Don Mills

My goodness, hasn’t The Globe and Mail come a long way in the education of the masses! We now get Ritchie Yorke and his glorified sexual review with our morning coffee. Do you really think your readers find this type of article interesting? At 27 I didn’t think I was too far removed from the world, but Mr. Yorke might as well have been talking about Mars!

Kitchener

The letter from R.C. (Pop Music and Sex—May 23) is an example of the silly stand taken by the self-appointed voices of public conscience in the name of morality. Yes, by all means let’s keep a “reasonably clean format” in the press. Let the “obvious illiterate types” shock and impress our children with all that “filth and depravity,” but don’t, oh please (delicate shudder), don’t spell the dirt out in the newspapers to shock the mature citizens who “prefer wholesome and decent conduct.”

A question for R.C.: If it was discovered by your neighbor that your adolescent son or daughter was associating with known degenerates, wouldn’t you be grateful to have the facts brought to your attention? The article, rather than aiding and abetting this moral madness, is a warning to parents and educators of our young that there is something very rotten in the entertainment (?) world when wandering groups of vulgar exhibitionists not only cheapen their own musicianship, but are given a free hand to con our kids into believing that this is what it’s all about.

Toronto