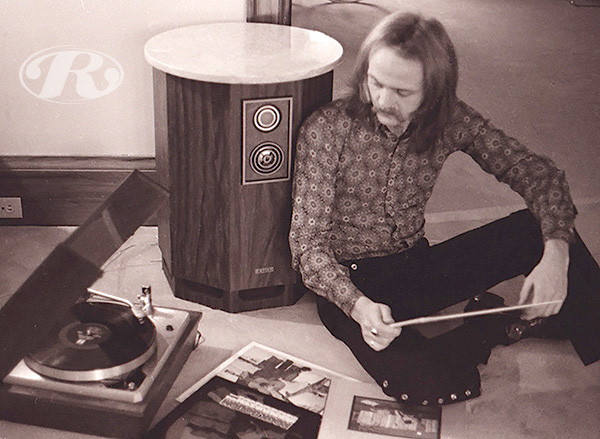

28 Jun Home in Toronto in 1976

Ritchie Yorke checks out the highs and lows of Empire speakers at home in Toronto in 1976.

Ritchie Yorke checks out the highs and lows of Empire speakers at home in Toronto in 1976.

In this issue, we continue our highly exclusive rap with members of Led Zeppelin, who new album – which is untitled – will be released in the next week or so.

In this final segment of the Led Zeppelin rap, we spent a good deal of time rapping about other artists future plans, the recent police fiasco in Milan, and a variety of other subjects.

GRAND FUNK

RY: What do you think of Grand Funk Railroad?

Jimmy Page: I’ve never heard anything by them. I know it sounds strange to admit that, but it’s true. I’ve only ever seen them doing a small segment on a BBC TV show I watched in England. It was at the time when they were just starting to get big in the States. It was difficult to judge from that.

RY: It would seem that Grand Funk is the only group able to come close to the Popularity of Led Zeppelin in the current scene. I mean, they drew more than 50,000 people to that recent concert at Shea Stadium.

Page: Yes, that’s true. But we heard that Humble Pie went down better with the kids at that gig.

RY: What about Black Sabbath? They’ve become very big in North America this summer.

Page: Really. That’s the first time we’ve heard that. They’ve done quite well in England, but I didn’t know they were drawing big crowds in North America.

Robert Plant: It was interesting to hear of Canada’s Prime Minister Trudeau getting together with the guys in Crowbar. Something is definitely happening here. Do you think we could get to meet him?

RY: Maybe. Who knows?

Plant: It would be nice if we could.

RY: What do you think of the current U.S. scene as you’ve seen on this tour?

Page: It’s hard to say really. The sort of scene I’d like to see is where all the different facets of the arts in the musical sphere are accepted readily by the media and the public. As it stands at the moment, it’s because of the press that there has to be one particular thing in vogue at any one time. As soon as that one thing becomes really popular, that’s it; you’ve got to find something else, something new. And then as soon as that is exposed and everybody knows about, it’s time to find something new again. It’s the old esoteric thing.

Unfortunately, the whole thing that is happening with us is the same as the James Taylor thing – but a complete opposite. Suddenly people are starting to say: ‘Hand on, he’s a damn good lyricist and a good song-writer, but on stage, he sounds very samey after about 40 minutes.” And now of course, all the people that were waving the flag are, you know, sort of crapping themselves a bit.

I blame the press for the whole stagnancy that frequently comes over the music business. It’s totally because of the press. Just let the musicians and the people get on with it – which is all the people ask for. And then everything would be accepted… and there’s so much happening in the music scene when you think about it.

RY: It’s quite remarkable when you consider that the biggest groups in the world, yourselves included, are continually ripped apart by the U.S. critics, for no apparent reason other than that they are incredibly successful.

Page: That’s not really our fault.

John Paul Jones: It’s just something to write about really.

RY: The sadness is that there are so many frustrated musicians getting into print with invalid criticism, which is not in the least constructive.

Page: Many critics seem to let their personal tastes jade what they’re seeing and hearing. It’s that whole thing of being put in a bag. Unfortunately, people are so trendy… that’s the terror of it all really.

There always seem to have to be a trend to follow. And if what you sing on that stage doesn’t comply with what they consider should be the particular trend, they tear it apart. Of course, these people should not be allowed anywhere near a pen or a typewriter or the press, because what they’re saying and doing is just totally the opposite of hat’s going on in the scene, and what’s going down. I mean, it’s like me going along and trying to write up a report on… well. I don’t know.

RY: It’s such a pity that not only do the majority of critics have no technical knowledge of the music, but they also have no feel for it. And the feel is the most important thing of all. But surely it can’t be as bad in England as it is in the States.

Page: It is.

RY: But at least there is some respect in Britain for success.

Page: We’re not asking for their respect. I mean, criticism can be great… valid criticism that is. I said it before and I’ll say it again – if I play, I know that I’ve played badly, and when I play well, I know I’ve played well. According to my own capabilities.

But people shouldn’t go along expecting an enigma when they see this bloke on the stage, and expect to see the epitome of what they consider to be the best of rock guitar. They should realize the bloke is only a human being – another struggling musician trying, trying, trying to better himself. That’s why there’s always this big race about who’s the best. There’s nobody who’s the best – nobody’s the best. Because there’s always somebody who’s got a particular field who’s better than the bloke who’s claimed to be the best. That’s what so good for me – that’s what makes the whole scene for me. But for these others, who always have to classify everything…

ERIC CLAPTON

RY: That would seem to be the reason that Eric Clapton dropped out of the scene.

Page: Poor Eric.

RY: He just couldn’t hack it anymore.

Page: Well I dunno. I went through what I think Eric may have gone through — it’s just the fact that suddenly everything you pick up seems to be going sour. Everything you read. You know, you’re trying your hardest and everyone is just saying… well you know… putting you down every time you try something.

GEORGE HARRISON

And I think for everybody who is really trying their hardest and is reasonably sensitive into the bargain, it’s gonna do a lot of damage, and I think it certainly did a lot of damage to Eric. And I know another person it did do a lot of damage to – about three or four years ago – and that was George Harrison, who could hardly pick up a guitar because he just thought that everyone thought he was a joke. It was obviously totally untrue as far as the public went, but as far as he press went, there were these snide comments and all that sort of thing. I think it took him – well, he made a friendship with Eric and he went through the sitar thing, which was pretty valid and he did some good things on that. But as soon as he got with Eric, he became a ‘guitar man, and he tried and he tried and he tried. Now he’s having a go and he’s won through. Which is good for him if he’s got the strength and the will to persevere… but for some people, it could shatter them totally.

RY: It’s quite incredible that not only was George able to come through that trip, but has since emerged as the foremost Beatle of the present time….

Page: Well, as far as the public’s concerned, you mean.

RY: As far as acceptance goes, he’s had a huge album and the recent concert with Dylan in New York. He seems to have stepped into John Lennon’s shoes, as far as being in the right place at the right time.

Page: Yeah, but its funny that since their split, you can see how important it was when the four of them were together.

PAUL MCCARTNEY

I met Paul McCartney in New York recently and he was talking to me about the album he was doing — the second one, Ram. He said you can’t believe how hard it is when you’ve worked with people for that amount of time – the same four people working together – and you come up with a song. And you just say ‘alright, here it is’ and everybody just fits their bit and it’s there. I know exactly what Paul means, because it’s like that with us.

He said it was so difficult to get it together with all fresh studio people. And I can sympathize with him. I know what it was like when I was playing sessions in London. You could see that – the blokes would come in with their song, and every session musician would have to try and do his best. Obviously it wasn’t as good as the bloke’s own group, but some A & R man was saying ‘well there’s got to be the session men, the group don’t match up to the quality we require.’

RY: The North American scene was dominated this summer by a soft-rock philosophy at radio stations, and as a result, there hasn’t been any good hard rock singles happening.

Page: Oh really. I can tell you one thing – whenever a good rock ‘n’ roll single comes out in England, it goes to No. 1 everytime without fail.

RY: Maybe so, but here, the stations want soft rock and that’s all they’ll play. A lot of mediocrity has been making it lately.

Page: It will do… all the old schmaltz will start happening and you’ve only got the radio station’s to blame for that. I’m going to repeat myself time and time again because I think this is so important – radio stations and rock writers should just give an overall picture of what’s going on, without all these jaded opinions that comes in. All that ‘this is what’s happening man – forget everything else – put them down because this is happening. It’s so wrong man.

RY: The abundance of hype doesn’t help either. Everything that comes out is the greatest new thing since… and that whole trip.

Page: Yeah, you’re right. But I know what my personal record collection consists of, and it’s got just about everything. From ethnic folk music of the aborigines to Mahler. It’s all part of it.

RY: Mahler. That’s interesting. Have you seen the beautiful film, Death In Venice, in which Mahler’s music is featured?

Page: Yeah I did actually. Yeah.

RY: Which records are you playing the most these days?

Page: Page: All sorts of different things. Bert Jansch is often on. Paderewski. No, that hasn’t been on for a while. Lots of early rock… lots of that. All the Sun stuff – it still sends shivers up my spine… it really does. Every now and then, when I’m thinking – you might read a lot… I was going to say when you read a lot of press, you wonder what it’s all about. I stopped reading the press myself, because we were getting things like Melody Maker through the post and it was costing a shilling and it was just total masochism to read it. You know, I was paying a shilling and just torturing myself. So I gave up on all that, and I don’t do it anymore.

Anyway, you put on something like the early Presley records and you hear the phrasing, you hear the excitement, and everyone’s really into it. At the end of Mystery Train, you hear them all laughing —it’s fantastic. And I can still get into those records because I know the excitement and the feeling that was there in those early days when they really knew that they were breaking into something – a new form of music.

RY: There’s a group like that in Canada. It seems that a large number of groups around the world are into rock ‘n’ roll now – Elton John finishes his concerts with a rock medley, Procol Harum also, and so on.

Page: Yeah, it has become a bit of a vogue. Unfortunately too. People like Elton John should leave it well alone, I think personally. It’s very hard, dear me. That’s another story altogether.

ELTON JOHN

RY: What do you think of Elton John’s albums?

Page: His albums are really, really good. For what he’s doing. I wouldn’t fault them. For his bag. But when he stands up and in sort of a yellow jacket, pink suit, I mean pink trousers, and silver shows, then kicks over his stool, which I thought was an incredible sendup of Jerry Lee Lewis, thinking oh yes, great in crowd humor. Then suddenly you realize that he’s serious and it’s a bit of a comedown after watching all that other stuff.

RY: Are there any new groups emerging in England which have really impressed you?

Page: Yes, quite frankly there are, but my head’s spinning at the moment and I can’t bring anything to mind. If you asked me about American bands, I couldn’t even answer right now.

RY: We were saying earlier that you hadn’t even heard a Grand Funk Railroad album yet?

Page: That wasn’t a put down of the band, it’s just that in England they don’t get played. I’ve heard reports about them, but nothing that would send me to a record shop to buy them on the off chance that they are good. I’ll never do that again anyway with a record. And I advise everybody else to do the same. Never buy a record until you know it’s good. I just seriously and honestly haven’t heard a Grand Funk record. I don’t know what they’re up to or anything.

RY: What sort of things do you have lined up for the immediate future?

Page: I think these home recording studios are going to be a big step towards better things, and technically better things. I hope, for myself, anyway. It’s suicide, I tell you.

RY: Will the fifth Led Zeppelin album be released in a shorted time than the long gap between the third and fourth?

Page: We’ve been recording on and off for a year; not constantly for a year, but every now and again, we’ve said ‘alright, let’s go in and see what we can do’. Every sort of thing seems to be relative statement of what you are at that point… you know, what you’re up to then.

RY: Do you have any problems with old material coming out – I mean, looking back at a certain track and saying that’s not us now… let’s get something together which is where we’re at now.

Page: Yeah, well this is it… you could do that. Obviously one often feels that. But you’ve just got to think it’s a relative statement for the time … at the time it was right… OK fair enough. And what you’ve got to think of all the time is that the next one will be better, better, better. That’s all you can do really.

RY: You’re going to be doing more gigs from now on. Isn’t there an English tour coming up?

Page: Yeah, we had a big sort of discussion about it amongst ourselves, and the idea was just to keep working – doing a couple of dates a week around England so that we’ve never rusty. Because sometimes we’d really knock ourselves out doing five days a week and all that in America, and then going back and really be knackered and have a month off and still be knackered. Then when it came to do a date you’d be rusty and crapping yourself. But now the idea is just to keep it ticking over nicely, and you’re always in trim… you can always keep practising at home and building it all up.

RY: What really happened with that mysterious J. P. Jones album?

Page: That’s quite a long story.

Paul Jones: It certainly is.

Page: You see, there’s this guy in England called John Paul Jones who made an album and tried to trade off our name. Our John spent a lot of time trying to stop it coming out, and in the end they released it under the name J. P. Jones. The next thing we heard was that it was coming out in the States, and we forced them to withdraw it. The strangest thing is that it was on Cotillion label, one of the Atlantic subsidiaries.

RY: That’s strange … Atlantic picking up a record like that when it already had Led Zeppelin selling millions of albums.

Page: Dollars… dollars.

MILAN RIOT

RY: In summary, I wonder if you’d mind telling us what actually went down at that recent concert cum police riot cum war in Milan, Italy?

Page: The policing of the people was what initially ruined it. It wasn’t until the brave few rushed forward that things started to happen. But I’ll give you the whole rundown on it. We were playing on the grass in a huge football ground. There were five or six groups before us, and it was sort of a festival thing which had been apparently organized and sponsored b the Government.

We went out on stage an started playing, and suddenly there was loads of smoking coming from the back the oval. The promoter came out and said tell the to stop lighting fires. So like twits,, we said into the mikes, ‘Will you stop lighting fires, please. The authorities might make us stop and all that sort of thing. So be cool about it, stop lighting fires, and we’ll carry on playing.’

Anyway, we went on for about another 20 or 30 minutes. Every time they’d stand up for an encore, there’d be lots of smoke. What it really was, as it turned out, was the police firing tear gas into the crowd

We didn’t know at the time – we just kept saying repeatedly ‘would you stop lighting those fires’. Twits, you know.

Paul Jones: The eyes were stinging a bit by then though.

Page: This was it. Until the time when one thing of tear gas caught the stage are – about twenty or thirty feet from the stage – and the wind brought it right over to us… we realized what was going on then.

Paul Jones: We kept on playing though.

Page: Oh we kept on playing. True to the end, the show must go on. But the whole thing was we saw this whole militia as we came into the gig at the beginning, and I said to the: ‘Look this is absurd. Either get them out or get them in trim or there’s gonna be a nasty scene.’ And what’s more, there was a backstage area that seemed to be swamped with everybody. You could hardly move through it, there was so many people. I said if you’re going to have the militia, at least get them to keep the backstage area free.

Well anyway, we were playing and then we said ‘Blow this, it’s got into tear gas. Let’s cut it really short.’ So we did one more number, then we went into Whole Lotta Love, and they all jumped up. At this point, there had been forty or fifty minutes of tear gas coming in and out, lofting about… and somebody threw a bottle up at the police. It was to be expected since the crowd had been bombarded for no reason – for no reason at all. And of course, as soon as the bottle went up, that’s what they’d been waiting for. Whoosh… there it went… all over the grounds – thirty of forty canisters of tear gas all going at noce. This tunnel that we had to escape through was filled with the stuff. It wasn’t done purposely, it’s just the way that things went. It was on another level and we had to run straight through this tear gas to get to the other side, which was a catwalk of rooms.

We didn’t know even then if were going to find chaos on the other side – people panicking and running. WE got in there, and people were trying to get into our door, into our room… probably thinking it was a place that was immune from the rest of it.

Paul Jones: The roadies were carried off in stretchers trying to save the gear. You see, they’d cordoned all the audience right around the back. There was a big line of police holding them there, and the only way they could go was forward, onto the stage. They forced something like 10,000 people up onto the stage.

Page: And our roadies were running around trying to save our instruments.

RY: It’s likely to be a while before you play Italy again?

Page: It’s a word that’s never even mentioned in my hearing. It causes a big argument… or a nervous breakdown.

Paul Jones: It was a war.

Page: Right, it was a war. And to top it all off, after all this, a reporter came back, a guy who’d seen the whole thing and knew exactly what had happened, and knew that the police had started it. He had the cheek, the audacity, to come into the bar where we were resting – we were completely shattered emotionally – he came in and said, ‘what’s your comments about that.’ Of course we just tore him apart, saying ‘C’mon, you saw it… now you write it up… don’t ask our opinion… You’ve got your own.’ But he kept on saying he wanted a comment for us.

RY: Did you give him one?

Page: No. But he almost… he almost had a bottle smashed over his head.

Soon, Led Zeppelin’s guitar star, Jimmy Page, exclusively gives his candid and decidedly controversial views on Elton John, Grand Funk Railroad, Black Sabbath, a recent Milan police riot and rock concert, pop critics, James Taylor, frustrated musicians, Eric Clapton, head changes through superstardom, George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Rolling Stone magazine, Gustav Mahler, the old Sun label stuff, Melody Maker, Pierre Trudeau, and much more. This world exclusive interview with the top band in the music business will continue in our next issue. And you won’t find it anywhere else.

RY: Jimmy, let’s firstly discuss the fourth Led Zeppelin album? Will it be called Led Zeppelin 4?

JP: No.

RY: I had an idea you might get off that bandwagon. What will it be called?

JP: It’s not going to be called anything.

RY: Really.

JP: It’s a non-entity in the marketplace. It’s not going to have a title. There’s four rooms or symbols on it, and each of us has picked out one. They’ll be on the inside of the dust jacket. There’s no writing at all on the outside cover. Apart from the building with one of the posters for the OXFAM thing, which says that everyday somebody receives relief from hunger you know, the one I mean, where someone is lying dead on a stretcher. Unfortunately the negatives were a bit of a blur… you can just about make it out if you’ve seen the poster before. It’s like a puzzle. But there’s no writing on the jacket at all.

RY: How about running down some of the tracks on the album?

JP: Track order. Well, firstly, there’s Black Dock which we played tonight and have been doing at some of the gigs. It’s a bit of hairage… a bit of a hairy one which John Paul Jones worked out the impossible part of the riff. It’s quite a hairy one really, compared to some of the other things on the album.

And then there’s one called Rock and Roll which we occasionally do on stage. It’s just what it says. Just a rock ‘n’ roll thing. It’s really quite good.

Then there’s Battle of Ever More with Sandy Dennis (of the Fairport Convention) singing. It’s just Robert and myself. I play mandolin, and Sandy sings with Robert. That’s a quiet one.

Next comes Stairway to Heaven, a rocker which we did tonight. It’s nice.

RY: Who wrote Stairway to Heaven?

JP: Well, everyone put in a bit really. Robert wrote the words, which is the key to it. Everything we do is really a mass co-operation I suppose. Everyone gets a say in everything. That’s how it usually is anyway. That’s what the group’s about really.

Side two opens with Misty Mountain Hop, which we’ve never played in the States or Canada. We have done it in some European concerts though.

Four Sticks is a thing which John Bonham plays with four drum sticks literally . . . two in each hand tearing along like mad. John Paul Jones put in some Moog synthesizer in a small section as well.

Then there’s going to California, which we did tonight. It’s an acoustic thing.

The side finished with When the Levy Breaks. It’s an old Memphis Minnie and Kansas John McCoy song… I first hear it done by Memphis Minnie on an album.

It’s sort of changed a bit now. Robert sings the same words as Memphis Minnie, but the whole arrangement is completely different. But Robert sings it in Memphis Minnie fashion so she’s getting a credit as well.

You’ll probably feel familiar with the other things. You’ve heard three of the tracks? What do you think? Do you think it’s a new departure or is it what you expected it to be?

RY: I think it’s great. There was a bit of each. There’s a little of what you expected, and then you’d hear something else and say, Hey that’s new and nice. I really got off on the tracks.

But how do you personally feel about this new album, as compared with your three earlier LP’s?

JP: Personally I lived with it for so long now – and seen so many mess ups by other people in the process of getting it together – that my senses have been battered into a pulp. I can’t even hear it anymore. It’s become like that. I don’t mean I can’t put it on and listen to it. I mean, I can’t get anything out of it at all. It’s really a dreadful state to be in.

But the fact is that there were so many foul ups by engineers… basically engineers. Andy Johns deserves to be hung, drawn and quartered, for the fiascos he’s played. Which is a shame because everyone was dead keen. But it just sort of dragged on and on because of mess ups that he made.

For instance, there was a statement that he made that ‘I know the place where we should mix this’ and we went there and wasted a lot of time. I won’t tell you the place because it’s no fault of the studio. He convinced us all that this was the place… the best place in the world… the best room… which is all we’re going for… the room I mean. With the right room you can hear the tape true to form and the record will sound exactly the same as that room.

And of course, it didn’t. And we wasted a whole week wanking around. It’s totally unforgiveable. From that point onwards, he crapped himself and he disappeared. We had to find a new engineer to tie it all up. That’s when the fiasco started because I was pretty confident after that week that it sounded alright to me. In that room, it had sounded great anyway. The trouble was that the speakers were lying. It wasn’t the balance – it was the actual sound that was on the tape. When we played it back in England it sounded like it had gone through this odd process. I don’t know, all I can put it down as, is the fact that the speakers and the monitoring system in the room were just very bright, and they lied.

RY: How long ago did you start working on the album?

JP: Some of the tracks were started in December. That was at the Island Studios in London. I can’t remember it all. We’ve got such a backlog of stuff on tape now, that even when we release the new album, we’ll still have a lot in the can.

Anyway, after Island we went to our house in Hampshire, a place where we have often rehearsed, and we decided to take the mobile studio truck there because we were used to the place… we’d often rehearsed there, we lived there sometimes, and we just set the gear up. We took along the Rolling Stones’ mobile truck. Then as we thought of an idea, we got it down on tape right away, and a lot of tracks came out of that. Almost everything on the album.

In a way, it was a good method of doing it. The only thing wrong was that we got so excited about an idea, and we’d rush to finish its format and get it on the tape – it was like a quick productivity thing. We got so excited about having all the facilities there.

What we needed was about two weeks solid with the mobile truck. We only actually had about six days, but we should have made it two weeks. We needed one full week to get everything out of our system and getting used to the facilities and then really getting together in the second week. That’s probably what we’ll do in the future, now we know the facilities we have available. John Paul Jones is getting a studio put in his house, and so am I. It seems to be the answer really.

You need the sort of facilities where you can have a cuppa tea and wander around the garden and then come in and do whatever you have to do, instead of walking into a studio… down a flight of steps into a fluorescent lights and opening up a big door that’s soundproof and there’s acoustic tiles everywhere.

With ordinary studios, it’s like programming yourself, as you walk down those stairs, that you’re going to play the solo of your life, which you very rarely do. It’s the age old problem that recording studios are the worst place to record. It’s the hospital attitude that studios have.

RY: Keith Richard was saying recently that he thinks the Stones’ mobile truck has shown that conventional studios are obsolete. After all, the environment is so important and studios are usually so cold and impersonal.

JP: That’s the whole thing. I personally get terrible studio nerves. Even if I’ve worked the whole thing out at home beforehand, I get terribly nervous playing anyway. But when I’ve worked something out at home which is a little above my normal capabilities, when it comes to playing it at the studio, well – to use of our favorite expressions – my bottle goes. If it’s something that you can just knock off fairly easily, then fair enough. But when it gets a little more difficult – well. That’s one reason why I’m personally getting my own studio set up together at home.

It’s not going to be as expensive as I though it would be, and obviously everyone’s going to benefit from it. I’ll be able to go all the acoustic things at home – I’m mainly going to use the studio for acoustic things. Then I’ll just hand it over and say here it is. I’ve managed to pull it off. I suppose it’s the same thing with you, John?

John Paul Jones: Exactly.

JP: It’s just the studio nerves… having the home new environment….

The Nerves were instilled into you in the session days and you never lose them, soon as that red light goes on. It could be three years ago making all those dreadful records.

RY: How do you feel about the new album, John?

JPJ: I quite like them all actually, you know; any album by Led Zeppelin is alright by me really. Oh, it’s rocking on merrily. And here’s one more.

To be continued Soon….

Go-Set – Saturday, June 5, 1971

America’s many pushers of softer rock music are currently proclaiming the end of Led Zeppelin, and other dynamite-powered sock-rock acts such as Grand Funk Railroad, Bloodrock and Gypsy.

These anti-hard rock critics are pointing to the success of James Taylor (with a lone single and album Elton John, Cat Stevens and others, as evidence that gutsy rock is about to sink.

It s true that U.S. top 40 stations have recently begun to sound like middle-of-the- road (or adult) stations, but this is really no indication that hard rock is on the wane. Singles account for a mere 10% of the U.S. total sales on records, and the fact that top 40 stations are not too keen to program tough sounds like Led Zeppelin is really no indication of anything, other than the widening credibility gap between the top 40 programmer and his youth audience.

Ever since Led Zeppelin first blasted their way into North American music in early 1969, the critics have done their best to damn the English foursome. Their records are seldom reviewed by the prominent rock papers, and when they are reviewed, it is with caustic and demeaning phraseology. Despite sales in excess of 2-million copies on each of their three albums which is a record in itself — no group other than the Beatles has been able to stack up such huge sales figures in the U.S. — despite half-a-dozen SRO, attendance breaking tours, and despite what is undoubtedly the finest stage show in contemporary rock, the American media has done all it can to ignore Led Zeppelin.

This is especially true of the revered news magazines such as Time and Newsweek – whose atrocious coverage of the rock scene raises some serious doubts about the rest of their reporting on hard news. Time recently accorded James Taylor (or) more significantly the Taylor family) a front cover story.

Two years ago, the Band were given similar treatment. Yet neither (nor both combined) act has ever come close to approximating the tremendous success of Led Zeppelin.

The trouble with Led Zeppelin — at least as far as the media is concerned — is that the group plays very loud music with all the emphasis the Band so clearly lacked. There never was a louder, harder, or tougher group than Led Zeppelin, and to the grey-haired ears of the news magazine’s music critics, it was like water running off a duck’s back.

Nevertheless, Led Zeppelin has worn its popularity well. Guitarist Jimmy Page, bass player John Paul Jones, drummer “Bonzo” Bonham and singer Robert Plant are four of the straightest and nicest guys in rock. There are no pretensions, no hype, no special show for the group’s few media friends.

Being with Led Zeppelin is like being with four of your friends. You just talk about whatever comes naturally.

Led Zeppelin were the forerunners of the word-of-mouth rock promotion route. The group’s first album. Led Zeppelin, sold its two million plus with no hit single and very little airplay. The reason for this was that the kids knew about Led Zeppelin without reading the rock journals or listening to the radio.

On the first U.S. tour (in February-March 1969) Led Zeppelin played every place that would have them – sometimes for as little as $750 a night. That is miniscule compared with the group’s current asking price of around $50,000 per performance.

Jimmy Page once told me that the purpose of Led Zeppelin was to simply play some good music and do a couple of American tours for expenses and a few hundred dollars bonus. There were never any grand plans of conquering the world, at least in the eyes of the band members.

The manager Peter Grant there was a different purpose. A giant of a man physically (he weighs around 300 pounds), Grant is no mental midget. Grant looked at the then current rock scene, noted that Cream was curdling and Jimi Hendrix was more hung up than a hammock, and saw that there were no real exponents of hard rock on the horizon.

Grant knew as well as anyone that the hard core rock audience is not interested in folk-oriented artists or C and W singers — what it wants is high energy rock. Led Zeppelin simply, and possible accidentally, slipped into the vacuum left by the departure of Cream and Hendrix.

The second tour cemented Led Zeppelin’s small but ardent following, and the second album brought about top 40 airplay on the group. A single from the album, Led Zeppelin II, sold a million copies. It was, of course, “Whole Lotta Love.”

By the time, “Whole Lotta Love” had reached its peak, Led Zeppelin were as well established in North America as motherhood or apple pie. And their fame had spread internationally — they quickly became the top groups in such places as Japan, Australia and Sweden. Gold records flowed in from all over the world.

The publishing royalties alone were worth millions. Manager Peter Grant once told me that Led Zeppelin’s major source of revenue was publishing. “There are no expenses,” he explained, “you just have a girl in an office to answer the phone and the money rolls in.”

This really means something when you consider that Led Zeppelin has received more than a million dollars from the Atlantic label on record royalties alone.

Such huge sums often bring complacency to rock stars. But not Led Zeppelin.

In its third album, the group attempted to change its image a shade. The hard rock numbers still went down, but there were also a couple of softer tracks — as if to show the critics that Led Zeppelin wasn’t all Marshall amplifiers and air splitting energy.

Led Zeppelin III also produced another million-selling hit single, “The Immigrant Song.”

Led Zeppelin — without Time or Newsweek or even Rolling Stone — have left a tidewater mark on the world of rock which no future tidal wave can ever wash away. They have demonstrated that the media is rapidly losing touch with what turns on the kids, and they have shown that hard rock will always have a place in the core of contemporary music.

The group is currently working on its fourth album for summer release, and getting ready for yet another U.S. tour. There are also plans for a world tour, which would take in Europe, Japan and Australia.

The people who have long hoped that Led Zeppelin would just die or fade away have a lot more waiting to do. Far from being burst, the Led Zeppelin bubble may be only just beginning, at least on the global scene. And that, according to Marshall McLuhan, is where it really matters.

SOMETHING

A tribute from King Curtis is no insignificant gesture. He is widely regarded as the pop world’s No. 1 tenor sax man.

He has played on each of the historic, sales-spiralling recording sessions of Aretha Franklin, and it was he who arranged, and blew sax, on Aretha’s classic version of Respect.

King is appearing at the Coq D’Or for two weeks, taking a strong claim as the foremost blues bandleader on the circuit today.

On uptempo numbers, he would make a touch-typist envious as he punches on the saxophone keys with amazing speed and dexterity.

He holds a blue note for so long that one begins to wonder if he has an auxiliary air tank hidden away on his bulky frame. He plays with unquestionable enthusiasm, dynamic drive, and sensitive persuasion.

VERSATILE

He’s equally at home with ballad or beat. It might have been freezing outside, but inside there was a heat wave going on.

The act’s eight-minute version of Ode To Billy Joe may yet bring the poor boy back to life. King’s rendition of I Was Made to Love Her is even more compelling, carrying a Cassius Clay-class punch.

Memphis Soul Stew, a recent hit for the combo, came off like home made apple pie. The clincher was Soul Serenade, a tortuous yet tender ballad, which Curtis blew through on his saxello with almost naive sensitivity.

Toronto is obviously hip to the Curtis message; the club was packed with people of all ages, the over 30’s predominating.

PISTON

Curtis and the Kingpins are as tight as a hot rod piston, with comparable power. The group comprises Jimmy Smith on electric piano, Mervyn Bronson on bass, Al Thompson on drums, and Stirling McGee on guitar, all first- class sidemen.

Curtis also introduced a young female vocalist, one Ruby Michelle, who contributed more than adequate workouts on current contemporary favorites like Chain of Fools.

The music is down to earth. The group is the equal of anything, anywhere. Curtis is King for those who like good music well played.

It was the late afternoon of one of those dog days of late summer in Toronto – hot, humid and oppressive. Hardly any indications of the bitter winter winds and icy storms which would splatter regularly upon this lakeside metropolis in just a few weeks to come.

The interview was a last-minute affair, as superstar interviews tended to be in that ancient era of music promotion. The idea had been bandied around for weeks after I’d scored valuable points with the Hendrix organization for my coverage of Jimi’s drug bust at Toronto Airport for Rolling Stone magazine.

Then out of the blue, his lawyer’s secretary phoned from New York to see if I’d be available to talk to Mr Hendrix later that day. One was not to know, of course, that this would be the great musician’s final interview before he flew to London and that destiny which awaited him post the Isle of Wight festival.

Nonetheless your youthful and respectful reporter approached the task with a degree of trepidation, knowing Jimi’s intolerance for ignorance or undue assumption.

The results were revealing in many ways that I was not to comprehend until later. In some aspects, not until much later.

The guitar master was in notably good humour and appeared willing to talk about anything I cared to mention during our discussion. No matter where the flow meandered in the wide-ranging interview, it didn’t appear to phase him.

He said that he’d been spending his time “thinking, daydreaming, making love, being loved, making music and digging every single sunset.” It all sounded almost too idyllic to be true against a background of increasing street violence.

Jimi had clearly been giving more than passing consideration to the exalted position he had so rapidly assumed in the pantheon of rock. And the inevitable injustice of living with being one of the lucky ones, while so many others struggled.

“I feel guilty when people say I’m the greatest guitarist on the scene. What’s good or bad doesn’t matter to me – what does matter is feeling and not feeling. If only people would take more of a true view and think in terms of feeling. Your name doesn’t mean a damn : it’s your talent and feeling that matters. You’ve got to know much more than just the technicalities of notes : you’ve got to know sounds and what goes between the notes.”

Jimi made it abundantly clear that he was fed up with public expectations of him, but appeared to have transcended the issue. “I don’t try to live up to anything anymore,” he said, obviously buzzed by his newfound freedom. “I was always trying to run away from it. When you first make it, the demands on you are very great. For some people, they are just too heavy. You can just sit back – fat and satisfied Everyone has that tendency and you’ve got to go through a lot of changes to come out of it.

“Really man,” he continued, ” I’m just an actor… the only difference between me and those cats in Hollywood is that I write my own script.

“I consider myself first and foremost a musician. My initial success was a step in the right direction, but it was only a step, just a change. It was only a part of the whole thing – now I plan to get into many other things.”

The clash between body and beat was bound to come in Jimi’s colourful and erotic career. The classic Hendrix we first saw – all unforgettably dashing and devastating and sizzlingly defiant – was an image makers’ dream. The uncompromising way in which he performed, it looked as though every twitch of the bushy eyebrows, every thrust of the velvet-panted knee, every shake of the tousled frizz, had been meticulously formulated by a motley crew of assorted PR and promotion types, under the collective influence of a super fine batch of acid.

His concert persona, with the biting of the guitar strings and the complete overshadowing of all but Presley in what had gone before on the rock pile, was as precise and as phallicly-stimulating as a missile countdown. He whipped the audience into an absolute frenzy and left them as limp as a fading rose on a boiling summer’s noon.

There at least two personas of Hendrix – the electrifying live performer and the studio genius. They didn’t necessarily have to inter-relate. “When it all comes down to it, albums are nothing but personal diaries,” he insisted

“When you hear somebody making music, they are actually baring a naked part of their soul to you.

“Are You Experienced? was one of the most direct albums we’ve done. What it was saying was ‘let us through the wall man, we want you to dig this.’ But Ikater when we got into other things, people couldn’t understand the changes. The trouble is that I’m a schizophrenic in at least 12 different ways and people can’t get to it.

“Sure each album comes out (sounding) different, but you can’t keep on doing the same thing. Everyday you find out this and that and it adds to the total (mental) picture you have. Are You Experienced? is where my head was at a couple of years ago. Now I’m into different things.”

One of those things which concerns him most acutely is the relationship between the earth and sun and mankind. “There’s a great need for harmony between man and earth. I think we’re really screwing up that harmony, by dumping garbage in the sea and air pollution and all that stuff. The sun is very important – it’s what keeps everything alive.”

It is no coincidence that Jimi’s final studio endeavour has just been released under the title of First Rays of the New Rising Sun. It was the album he was completing when he died He talked about it briefly during our conversation.

“All I know is that I’m working on my next album. We have about 40 songs in the works, about half of them completed. A lot of it comprises jams – all spiritual stuff, very earthy.”

Scoffing at prevailing rumours that he had been contemplating taking a year off, Jimi did cast light on an immediate ambition, a big trip in its own right.

” I’m gonna go to Memphis,” he declared in a curious tone. “I had a vision and it told me to go to Memphis and meet my maker. I’m always having visions of things and I know that it’s building up to something really major.

“I think (organized) religion is just a bunch of crap. It’s only man-made stuff, man trying to be what he can’t. And there are so many broken down variations All trying to push the same thing, but they’re so cheeky – all the time adding in their own bits and pieces. Right now I’m working on my own religion which is life.

“People say I’m this and I’m that but I’m not. I’m just trying to push the natural arts – rhythm, dancing, music. Getting all that together is my thing.”

Jimi wasn’t too impressed with the state of pop music circa 1970. ” I think too many musicians are getting on bandwagons,” he retorted. “Now is the time to do your own thing You know man, sometimes I can’t stand to hear myself because it sounds like everyone else I don’t wanna be in that rat race !

“What I particularly don’t like is this business of trying to classify people. Leave us alone. Critics really give me a pain in the neck. It’s like shooting at a flying saucer without giving its occupants a chance to identify themselves. You don’t need labels man, just dig (the broad spectrum of) what’s happening.’’

I suggested to Jimi that during the course of our 45-minute interview, he seemed a lot happier and more relaxed than he’d been in earlier conversations. “Yeah man, and I’m getting more happy all the time,” he confided “I see myself getting through all the drastic changes, getting into better things.

“I like to consider myself timeless. After all, it’s not how long you’ve been around or how old you are that matters : it’s how many miles you’ve travelled. A couple of years ago. all I wanted was to be heard. “Let me in’ was my big thing Now man, I’m trying to figure out the wisest way to be heard.”

[Wed, Arp. 15, 1970]

Ottawa Journal

OTTAWA – Not since the glorious, glamorous, heyday of the Beatles had there been anything like it.

An opening night audience of 19,000 people in Vancouver, surpassing the Beatles’ house record by more than 2,000. In Los Angeles, more than 20,000 fans, and a cheque for $71,000, topping Cream’s one-night record fee of $70,000 at Madison Square Garden.

DISADVANTAGE

In Montreal the night before last, a crowd of almost 18,000 – smashing the house record. And then last night, amidst exams and Ottawa’s traditionally small turnouts on weekdays about 8,000 crammed into the civic centre.

Who was causing all the fuss? Who else but Led Zeppelin, steamrollling its way across North America on its fifth tour in 18 months. This jaunt will earn the group in excess of $1.2 million for 26 concerts.

Toronto missed out this tour, and it was our loss. But to be fair, Toronto has seen the Zepp three times previously, while Vancouver, Montreal and Ottawa missed out.

The Ottawa gig was not the best the group has ever done, but they were at considerable psychological disadvantage in playing a massive stark concrete arena such as the civic centre. It may be the ideal spot for a hockey game, but it was too artistically cold for a musical event such as this.

Billed as an evening with Led Zeppelin, the concert was just that. There were no supporting acts, no intermission. Just two solid hours of smashing, splattering rock music. The sound ripped out of six massive speakers, infiltrating anything which stood, sat or lay in its way.

The repertoire was almost all well-know, which added to the impact. Culled from both the Led Zeppelin albums, it was delivered with style because of the sheer waves of volume with finesse.

POTENT

Of course, there is nothing wrong with volume in rock. Contrary to what most critics claim, volume is used in rock not to cover up lack of expertise but to add sting to the message.

In this area, there has never been a more potent group than Led Zeppelin. Perhaps this is why no other group since the Beatles, or before for that matter, has been able to generate the sort of excitement and energy which Led Zeppelin is offering right now.

Backstage, after the show, it resembled the winners’ dressing room after a Grey Cup final. There were TV cameras and radio microphones, autograph hunters thrusting forth posters and hot dog wrappers, and businessmen tossing in business cards.

Amidst the chaos, I managed to learn from Jimmy Page that a third Led Zeppelin album to be called Zeppelin III, will be released in July.

“It will have more variety than the other two albums,” Page said, “and there’ll be more emphasis on acoustic guitar.”

Robert Plant cut in, through the clatter, “and there’ll be some nice vocal harmony things.”

Then the group got into the limousines and headed back to the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, where they are occupying the same suite used by John and Yoko.

Continuing four-part series on Led Zeppelin, I turned to lead singer Robert Plant, who is regarded in some quarters as rock’s most provocative sex symbol since Jim Morrison (but wait till you hear what he has to say about that!).

RY: DID YOU EXPECT TO MEET WITH SUCH STAGGERING SUCCESS?

RP: Never! I don’t think anyone could expect that really. Not even Jimmy, and Jimmy already knew that American audiences were much more responsive to hard work. But none of us really expected this. Just band! And we really never knew how big we were.

You can’t really realize it until you come to each individual town that you have never been in before and people are running down the street banging on your car windows and all that. And when you get a fantastic reception the moment you walk on stage, you start to realize just what’s happening. I could never have dreamed of anything like this.

RY: WHAT WERE YOU DOING BEFORE LED ZEPPELIN WAS FORMED?

RP: I was working immediately before LZ with a group called Alexis Korner and we were in the process of recording an album with a pianist called Steve Miller, a very fluid thing – nothing definitely set up. We were going to do a few festivals in Germany and that sort of thing. Before that, I hadn’t dome much at all. I’d cut three singles which I prefer to forget. I want to leave them in the dimmest past!

John Bonhm and I worked together for a total of about 2 1/2 years. It was a period of trying to find what I wanted to do musically. You know, you go through the initial thing where you want to get up on stage and scream your head off, and the next minute you want to play blues and you finally find that everything is a means to an end to what you really want to do musically… once you’ve reached it.

So I feel my first four or five years were finding out what I wanted to do. You could either end up going completely into the pop field on a commercial trip, or just stick to what you liked musically.

RY: HAVE YOU NOW FOUND YOURE MUSICAL NICHE?

RP: I think I’m finding it. The first year of LZ has made me see a lot more of what I want to do. I think this year has been much more valuable to me than the other five because for the first five years nobody really wanted to accept what I was doing, even though we were doing a sort of Buffalo Springfield – Moby Grape sort of thing.

In England, nobody really wanted to know, they just said it was noise with no meaning; and to me, it was the only noise with meaning. The Springfield and the Grape really knew what they were doing.

LZ has given me a chance to express that in lyrics on the second album and when we do the third album I hope to get that thing even more to the point of what I’m trying to get into. Gradually, bit by bi, I’m finding myself now. It’s taken a long time, a lot of insecurity and nerves and the “I’m a failure” stuff. Everybody goes through it. Even Jimmy did, when he was with the Yardbirds, but now everything’s shaping up nicely.

RY: WHEN YOU STARTED THOUGH, EVERYONE IN NORTH AMERICA THOUGHT THIS WAS JIMMY PAGE’S BAND. THAT WAS THE IMPETUS WHICH LAUNCHED YOU HERE. IT MUST HAVE MEANT YOU ALL HAD A GREAT RESPONSIBILITY TO PROVE YOURSELVES INDIVUALLY, AS BOTH PEOPLE AND MUSICIANS.

RP: Yeah, but it was really good, because, well, obviously we owed a lot to Jimmy in the first place because, without him, we couldn’t have gone into the right places initially… Because people like Spooky Tooth have had such a hard time trying to get any sort of reputation in the States, and eventually all their inspiration goes.

Spooky Tooth came over here in the summer and did about seven gigs in as many weeks. It was very bad for the band.

With Jimmy’s reputation, we could go into the proper clubs, but had Jimmy been the only member of LZ who was any good at all, it would have been pointless. Fortunately each of us shone in our own little way, if that’s what you can call it, and the audiences said: “Wow, there’s Jimmy and he’s brilliant” and they look around and they take everybody else how they want to.

Obviously on the first tour, it was all Jimmy, Jimmy, Jimmy, which is fair enough because he deserved it, and then on the second tour people started taking an interest in the other members of the group and then with our stage act, well we’ve had some criticism of that.

The thing is that after a while you personally start going out on the stage and you can feel what’s going to happen. The moment you set foot on stage you can sort of let go, and the audience is like a piece of blotting paper and what makes it is what you give it, and you’ve gotta give it good.

Each of us has a different personality which comes to the fore. Like John, when he jumps into the air above his drums. Everybody now knows each member of the group for his musical ability and for himself, I think.

RY: ROBERT, YOU HAVE BEEN DESCRIED AS THE MOST IMPORTANT NEW SEX SYMBOL IN POP SINCE MORRISON. DOES THIS REALLY GET TO YOU? OR DO YOU TAKE IT LIGHTHEARTEDLY?

RP: Yeah, well, don’t you think it’s the end of you life once you take it seriously, that sex symbol thing. If any musician goes on stage feeling that; I mean, you can take in all that applause at face value and it can turn you into a bad person, really it can.

TERRIBLE HARM

All this sort of popularity can do you terrible harm and I treally thought that it would do once we started getting off. I though, “God, if this keeps going what the hell will happen to me?”

You can go right off your rocker and you can start to think – “Here I am and I’m the greatest singer in the world” and all that. But it’s not worth doing that because there’s always someone who can come along and will sing better than me and I fully realize that. So all you can be is honest and be yourself.

If there’s some nights when I don’t want to say anything to the audience then I don’t. But I don’t make it noticeable.

I don’t really know how people think about sex symbols. If they can see your pelvis then that must make you a sex symbol… because I’m the only one of us that doesn’t have a guitar or drums in the way of mine. I suppose I started with a bit more chance than anybody else in the band.

You can’t take it seriously simply because you read all these things about it. You just get into your music and the sexual bit isn’t an apparent thing. It’s not what we’re there for.

RY: YOUR STAGE ACT SEEMS TO BE GOING THROUGH SOME CHANGES, AS COMPARED WITH THE FIRST COUPLE OF TOURS.

RP: Yeah. I think that what we’re doing now is what each one of us wants to do. I think people expect us to be a lot more arrogant than we are. A lot of people say “Yeah well they’re alright but what about all that laughing and jumping around they do.”

There seems to be a label that goes with music that’s intense. People are expected to stand there looking as through they’re out of their minds. If ever I was to go out of my mind, I’m sure I wouldn’t just stand there like that – so it’s like a big play act and we mustn’t play otherwise we’ll run away with ourselves like Jim Morrison did.

RY: DO YOU THINK MORRISON TAKES HIMSELF TOO SERIOUSLY?

RP: Oh yeah. We only played with the Doors once in Seattle and it seemed like he was screwed up. He was giving the impression he was into really deep things like Skip Spence of Moby Grape. You can get into a trip of your own that you don’t really realise what’s going on in the outside world.

Morrison went on stage and said “Fuck you all” which didn’t really do anything except make a few girls scream. Then he hung on the side of the stage and nearly toppled into the audience and did all those things that I suppose were originally sexual things but as he got fatter and dirtier and more screwed up, they became bizarre.

So it was really sickening to watch. My wife and I were there watching and we couldn’t believe it. I respected the Door’s albums, even though they’re not brilliant musicians, and, as I said, that doesn’t matter. What Morrison was doing on record was good.

Over all our heads

The tracks “Cancel My Subscription To The Resurrection” was great, but now he doesn’t get into any of the things from the past, and the sexual thing has gone. He was just miles above everyone’s head. It seemed that he realized the Doors were on the way down.

He went on stage with that opinion and immediately started saying all those strange things which nobody could get into. There were one or two people there crying: “You’re God, you’re King,” and I was thinking, “Why?”

Then the Youngbloods went on stage and wiped the audience out because they were so warm. They’d laugh and the audience would laugh. That’s how music should be. It isn’t a real serious thing. We’re not over here to have a bad time. We’re over here to have a good time and people pay money to have a good time as well.

RY: BUT THERE HAS TO BE SOMETHING ELSE GOING DOWN. JIMMY AND I AGREED ON A THEORY ABOUT A GAP IN THE SCENE FOR HARD ROCK.

RP: You could say that and then again you couldn’t. There was such a difference, even on first hearing, between us and the Cream. There was an intense difference. Thrtr were other groups in the country at the time who could have filled the Cream’s place more specifically than ourselves.

RY: BUT YOU’RE INTO HARD?

Different things

RP: Well, I think individually, off stage, we’re into different things but it all comes out in the music. If you noticed, we had a C&W half hour the other night.

RY: THERE SEEMS TO BE A LOT OF YOUNGER KIDS TURNING UP TO YOUR CONCERTS?

RP: Yeah, the spreading of the gospel I suppose! It beats me why they come. I really think that the first album wasn’t commercial at all. You know, CS&N are for more commercial than LZ. In as much as the vocal thing is there to hand on to. With LZ there was all sorts of different things going on. Every member of the group was doing something different so it doesn’t strike you immediately as something…

RY: OBVIOUSLY YOU DID WHAT YOU WANTED AND THE PUBLIC LIKED IT AT THE SAME TIME?

RPL Yeah, that’s why I can’t see why the kids that came along got into it as strongly as we did and as strongly as the original audiences who came to see us when we first came over here. So you’ve got this stronger thing now. The audiences are really strange now. It worries me sometimes to see how it’s turning out. Go to concerts by Janis or the Youngbloods or Neil Young and you’ll still get the same people. So I suppose the audience is just fanning out more and more.

RY: YOU MADE IT IN AMERICA FIRST AND THEN BRITAIN. THIS HAS GOT A FEW PEOPLE UPTIGHT?

RP: Yeah, it has. You can imagine that England being the conservative place it is, the conservatism foes into the music as well. The musical journalists are still sort of dubious about this sort of music and they were thinking that it was a flash in the pan and they didn’t think it had any social relevance which it does.

Groups who go on stage and play music at festivals that says: “Down with the establishment” are immediately in the majority now – even in England.

RY: WHO ARE YOUR GREATEST INFLUENCE:

RP: There was a guy called tommy McClellan, who recorded on the Bluebird label for RCA in the 30s. His rapport, the way he completely expressed himself on record, was great ‘cause it was though he was saying “To hell with you,” all the time, and he was just shouting out all these lyrics with such gusto that even now, you could sit there and go “Corr.”

It’s the same with Robert Johnson. His sympathy with his guitar playing, it’s just like when you’ve a vocalist you have to be sympathetic with the musicians you’re playing with.

RY: B.B. KING?

RP: Not really. I like B.B. I like to listen to him, I like to hear him sing and I like him stalking and leading up to things like “Don’t Answer The Door,” where he does a big rap like that Isaac Hayes album, where he does a big thing for a long time. But B.B. King is a guitarist’s sort of singer really if anybody is sort of going to take things from him.

I always respected Steve Winwood I must admit. He was to me the only guy. He had such a range in the early days when Spencer Davis first became popular. They were doing things like “Don’t Start Crying Now” By Slim Harpo and “Watch Your Step” and “Rambling Rose,” Jerry Lee Lewis, and the whole way. Steven was one of the first people who wasn’t sticking to the normal, like the Hollies and all those groups who had been “dot dash, dot dash, follow the lines” and sang all the same thing every night.

And along came little Winwood, who was only a bit older than me, and started screaming out all these things and I though, “Gosh, that’s what I’ve been trying to do.”

RY: WHAT DO YOU THINK OF JOHN PAUL JONES?

RP: What a question! As a musician, incredible. His imagination as bass player is very good. Also as a pianist and organist, because he looks at the whole thing in a completely different way to me. I mean, the five lines and four spaces were never of any importance to me because I was a vocalist and I just hung onto the fact that it was an easy way out being a vocalist. You don’t have to know much, you just have to sing.

He comes from a different angle all together and even though it doesn’t apply to my singing he can be a definite influence on the group – if he cares he can be which is an interesting thing. Jimmy can read music and all that, but he’s more basic, more into blues and whamming out and writing the sort of thing I want to write, but John comes in and his rhythms and his whole thing from Stax and soul side of things, they give you the backbeat that you need so I appreciate that.

RY: BONZO?

RP: He’s a good sparring partner? (Laughs). We played together for a long time and I think this is the only band we’ve ever had, obviously, any success in. If I didn’t like him as a drummer I suppose he wouldn’t have been the drummer, because someone would have said no. So he’s got to be all right. Besides, he’s phone his missus in the morning to send a bunch of flowers to my wife.

RY: Jimmy?

RP: To begin with, when someone comes along and says: “Come with us; you’re going to make a lot of money,” you think he’s got to be joking, so you say okay. But in the beginning I held myself a long way off from him. The more you get into the bloke, although he seems to be quite shy, he’s not really. He’s got lots of good ideas for songwriting and he’s proved to be a really nice guy.

[Friday, April 10, 1970]

Ottawa journal

TORONTO – When they get around to evaluating rock music by year (in a manner of generalizing very common in the wine industry, e.g. ’67 was a great year for whites but the reds were a little bitter) 1969 is not going to be a year you’ll hear to often.

The last year, in fact, was one of rock’s least memorable periods. There was hardly a single worth mentioning (indeed hit singles seem to get worse by the month); Bob Dylan’s “Nashville Skyline” was not his finest album nor was it close; the Beatles’ Abbey Road was a magnificent effort yet many ineffectual critics still slurped of Sgt. Pepper.

They slurped, at least, until John Lennon came out and said that he thought every album since Pepper had been better than it, including “Magical Mystery Tour.”

The last year of the Sixties saw soul music sink to an all-time low, both in popularity and polarity. Aretha Franklin only made it to one record session, and the results weren’t heard until a month or so ago.

The Rolling Stones made a monumental album in “Let It Bleed,” but seemingly took it title too seriously. All the sharp incisions performed by Let It Bleed were completely overshadowed by the hatchet job at Altamont. Creedence Clearwater made it to the upper rungs with many albums, all of which sounded like the one before.

DEAR LITTLE Donovan came out against dope, hoping to pick up on the eight-year-old record market, which is just starting to be taped and has proved to be fertile soil for acts such as Three Dog Night, the Ohio Express, Tommy Roe, Shocking Blue, and the Union Gap.

Top-40 radio reached a swampy bottom. Didn’t you notice how the Golden Olden weekends sounded a hundred times better than regular programming? That’s because prior to the fawning of format radio, record producers made records with a lot of creativity and little regard for the current top 10.

When it’s all boiled down, the only really encouraging thing that happened last year was the unveiling of Led Zeppelin, England’s latest weapon in the war against American Rock. By year’s end, Led Zeppelin – a group unknowns apart from guitarist Jimmy Page – had become the most important new band since the Beatles, surpassing even Cream in popularity.

The group’s sudden success came after Cream curdled and Hendrix fell victim to well-fed delusions of grandeur. There wasn’t much of music’s usual hype, and there was even less critical acclaim for the Zepp.

Even now, it’s very much in vogue in rock critic circles to rip off Led Zeppelin as a noisy bunch of perverts from England. Even some of rock’s upper echelon of publications still seem to deny the existence of the Zeppelin. Initially, there wasn’t much serious critical evaluation of Led Zeppelin. They were just another stoned-out band from England into blues. Sure they had a guitarist from the Yardbirds but wasn’t Jeff Beck the man to watch from that trip? Scepticism, apathy, ignorance. Meanwhile, the Zepp had arrived and hit and left the charts coated with the debris of a hard-rock hurricane.

THE BAND’s concert price zoomed from a low of $250 in Januarsy of last year, to $25,000 at the start of their current, fifth tour. Both albums had sold in excess of one million copies by Christmas. And a single, Whole Lotta Love, went very close to a million.

The new tour will earn the group more than $800,000 and will take in Vancouver on March 21, Montreal on April 13 and Ottawa the following night.

Any day now, Sixteen magazine and all those other guides to the six-year-old mentalities will realize that Bobby Sherman, Dino Desi and Billy, and the Monkees are not what’s happening.

Right now, what’s happening in rock is very much in the hands of Jimmy Page, John Bonham, Robert Plant and John Paul-Jones. Without question, Led Zeppelin is the world’s most popular group, outside the Beatles, and no one knows anymore if the Beatles still are a group.

SOMETHING

A tribute from King Curtis is no insignificant gesture. He is widely regarded as the pop world’s No. 1 tenor sax man.

He has played on each of the historic, sales-spiralling recording sessions of Aretha Franklin, and it was he who arranged, and blew sax, on Aretha’s classic version of Respect.

King is appearing at the Coq D’Or for two weeks, taking a strong claim as the foremost blues bandleader on the circuit today.

On uptempo numbers, he would make a touch-typist envious as he punches on the saxophone keys with amazing speed and dexterity.

He holds a blue note for so long that one begins to wonder if he has an auxiliary air tank hidden away on his bulky frame. He plays with unquestionable enthusiasm, dynamic drive, and sensitive persuasion.

VERSATILE

He’s equally at home with ballad or beat. It might have been freezing outside, but inside there was a heat wave going on.

The act’s eight-minute version of Ode To Billy Joe may yet bring the poor boy back to life. King’s rendition of I Was Made to Love Her is even more compelling, carrying a Cassius Clay-class punch.

Memphis Soul Stew, a recent hit for the combo, came off like home made apple pie. The clincher was Soul Serenade, a tortuous yet tender ballad, which Curtis blew through on his saxello with almost naive sensitivity.

Toronto is obviously hip to the Curtis message; the club was packed with people of all ages, the over 30’s predominating.

PISTON

Curtis and the Kingpins are as tight as a hot rod piston, with comparable power. The group comprises Jimmy Smith on electric piano, Mervyn Bronson on bass, Al Thompson on drums, and Stirling McGee on guitar, all first- class sidemen.

Curtis also introduced a young female vocalist, one Ruby Michelle, who contributed more than adequate workouts on current contemporary favorites like Chain of Fools.

The music is down to earth. The group is the equal of anything, anywhere. Curtis is King for those who like good music well played.

The third member of Led Zeppelin to be interviewed in-depth is drummer John “Bonzo” Bonham, surefly the finest drummer to emerge since Ginger Baker. Once again, like co-Zepps John, Paul and Robert, he answered my queries frankly and willingly.

RY: WHAT WERE YOU DOING BEFORE LZ?

JB: Five months before LZ appeared I was playing with Robert Plant in a group called Band Of Joy. We did a tour as a supporting act with Tim Rose when he playing England. Then Tim went back home and we continued for a bit longer and then we broke up. Tim Rose was coming back for another tour and he remembered me from the Band Of Joy and offered me the job and I took it.

So Robert and I lost contact for about 2 or 3 months. The next time I saw him I was with Tim and he’s joined what was then the Yardbirds. He said they needed a drummer for a new group. About two weeks later he came with Jimmy Page to one of Rose’s concerts, saw my playing and then I got offered the job.

RY: WERE YOU SURPRISED AT LZ SUCCESS?

JB: Yes, very surprised. T the time when I first got offered the job, I thought the Yardbirds were finished, because in England they had been forgotten, but I though: “Well, I’ve got nothing anyway so anything is really better than nothing.” I knew that Jimmy was a good guitarist and I knew that Robert was a good vocalist so that even if he didn’t have any success, it would be a pleasure to play in a good group. And it just happened that we had success as well.

RY: HOW LONG HAVE YOU BEEN PLAYING DRUMS?

JB: Six years.

RY: WHICH DRUMMERS HAVE INFLUENCED YOU?

JB: Loads of drummers. I dig listening to drummers I know aren’t hald as good as perhaps I am. I can still enjoy listening to them and they still do things that I don’t do, so therefore I can learn something. I like Vanilla Fudge’s drummer, I like Frosty with Lee Michaels.

I walked into that club last night (Toronto’s Penny Farthing) and there was a group (Milkwood) whose drummer was great. He had such a great feel to the numbers. You know things like this happen all the time. You go somewhere and see areal knockout drummer.

RY: HOW ABOUT BAKER?

JB: I was very influenced by him in the early days because when I first started Baker had a big image in England. He was the first rock guy, like Gene Krupa. In the big band era a drummer was a backing musician and nothing else. And in the early American bands, the drummer played with only brushes in the background. Krupa was the first drummer to be in a big band that was noticed.

You know he came right out into the front and he played drums much louder than they were ever played before and much better. Nobody took much interest in drums really up until that thing and Baker did the same thing with rock.

Rock had been going for a while but Baker was the first to come out with that… a drummer could be a forward thing in a rock band and not a thing who was stuck in the back and forgotten about. I don’t’ think anyone can put Baker down.

I don’t think he’s quite as good as he was, to be honest. He used to be fantastic but it’s a pity the Americans couldn’t have seen the Graham Bond Organisation, cause they were such a good group – Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker and Graham Bond – a fantastic group.

Baker was more into jazz I think. He still is – he plays with a jazz influence. He does a lot of things in 5/4, 3/4. He’s always been a very weird sort of bloke. You can’t really get to know him. He won’t allow it.

RY: WHAT DID YOU THINK OF RINGO’S DRUMMING ON “ABBEY ROAD”?

JB: Firstly, I wouldn’t really guarantee that it’s Ringo playing because Paul McCartney had been doing a lot of drumming with the Beatles, I Hear. Let’s just say I think the drumming on “Abbey Road” is really good. The drumming on all the Beatles’ records is great. The actually patterns are just right for what they’re doing. Some of the rhythms of the new album are really far out.

RY: ARE YOU PLAYING MUSIC THAT YOU LIKE?

JB: Yeah. I think we do a bit of everything really. We got from anything in a blues field to a soul rhythm. Anything goes.

Jimmy will do a riff and I’ll put in a real funky soul rhythm there or a jazzy swing rhythm or a real heavy rock thing. It’s really strange.

RY: OUR SEEM TO HIT THE SNARE DRUM HARDER THAN ANYBODY AROUND. HOW MANY SKINS HAVE YOU BROKEN ON THIS TOUR?

JB: None. You can hit a drum hard if you take a short stab at it and the skin will break easily. But if you let the stick just come down, it looks as though you’re hitting it much harder than I am. I only let it drop with the force of my arm coming down.

But I’ve only lost one skin on this tour. That was a bass drum skin and that was because the beater came off and left the little iron spike there and it went straight through. But that snare skin has been on there for three tours.

When the bass skin went, we were into the last number, “How Many More Times,” and Robert was into his vocal thing just before we all come back in. It was a bit of a bummer.

RY: HOW DID YOU START PLAYING SOLO ROUTINES WITHOUT STICKS? DID YOU BREAK THEM ONE NIGHT?

JB: It did begin with something like that. I don’t really remember, I know I’ve been doing it for an awful long time. It does back to when I first joined Robert, I used to do it then. I don’t know why really. I saw a group years and years ago on a jazz programme do it and I think that started me off. It impressed me a helluva lot.

It wasn’t what you could play with your hands; you just get a lovely little tone out of the drums that you don’t get with sticks. I thought it would be a good thing to do, so I’ve been doing it every since.

RY: WHAT DO YOU THINK OF ROBERT PLANT?

JB: I could talk about Robert for days because I know him so well. I think we were 16 when we first met which is six years ago. That’s a long time. He knows me off by heart and vice versa. I think that’s why we get on so well.

I think when you know someone – when two people get together and know each other’s faults and good points – you can get on with them for a long time because nothing they do can annoy you when you’re already accustomed to it.

RY: HOW ABOUT JOHN PAUL JONES?

JB: We get on well. The whole group gets on well. We have our differences now and then.

But to me some groups get too close and the slightest thing can upset the whole group. In this group, we’re just close enough, without getting on stage and someone saying something and the whole band being on the verge of breaking up. That’s what happens when a group gets too close. You can get more enjoyment out of playing with each other if you don’t know everyone too well.

That’s why so many people like jamming. Sometimes it isn’t any fun anymore to play with a group you’ve been in for years. But with LZ, we’re always writing new stuff, doing new things and every individual is improving and getting into new things.

RY: WHAT DO YOU THINK OF JIMMY PAGE?

JB: I get on well with Jimmy. He’s very good. He’s quite shy in some ways to. When I first met him he was very shy. But after 12 months’ at it, we’re all getting to know one another. That’s why the music has improved a lot, I think. Everybody knows each other well.

Now there are little things we do which we understand about each other. Like, Jimmy might do a certain thing on his guitar and I’m not able to phrase with him. But in the early days i didn’t know what was going to come next.

But I still don’t know Jimmy all that well. Perhaps it takes more than a year to actually sort of know someone deeply. But as far as liking goes, I like Jimmy a lot. To me, he’s a great guitarist in so many fields. He’s not just a group guitarist who plugs in and plays electric guitar.

He’s got interests in so many kinds of music. So many guitarists wont play anything but 12-bar blues, and they think that’s it. And they have an attitude of when they hear a rock record of saying “Oh that’s a load of rubbish.”

Blues has got to be pure and they’re pure because they play it, but really that’s not true either. Some of the greatest musicians in the world have never played blues so you can’t really say that.

When we first came over here, the first American drummer I played with was the Vanilla Fudge’s drummer. He was one of the best I’ve ever seen in a rock group yet so many people put them down. Nobody wants to know, thinking they’re a bubblegum group.

Perhaps they were but you can’t get over the fact that they’re good musicians. No matter which way you look at it, they’re still good. Although they’re playing music that I don’t particularly like, I still admire them.

RY: ARE YOU FED UP WITH TOURING YET?

JB: No, not really. Sometimes it gets to be a bit wearing, but that’s only because I’m married and got kids at home. But I’ve never got browned off with the actual touring. I enjoy playing; I could play every night. It’s just that being away gets you down sometimes.

I enjoy going through different towns we haven’t been to before. But you get fed up with towns like New York where you’ve got to spend a lot of time. It just isn’t interesting any more.

The this part of our four-part series on Led Zeppelin is an interview with the man who made it all possible in the beginning, guitarist extraordinary Jimmy Page.

RY: WHERE DO YOU THINK YOUR FOLLOWING LIES?

JP: It’s hard to pinpoint really. At the beginning it was the underground clubs because that’s where we started. Obviously it’s spread by the amounts of people who come to our concerts. People are coming all over from schools and I don’t know where. The turnout is getting so big you wonder where everybody does come from. I suppose basically it was from the underground thing.

RY: THERE SEEMS TO BE A LOT OF YOUNG PEOPLE INTO YOUR MUSIC NOW?