IT WAS CHOICE, not necessity, which had me reading and puzzling on Christmas Day over Patrick Watson’s recent book, Conspirators In Silence. Two happenings of recent days make Patrick topical.

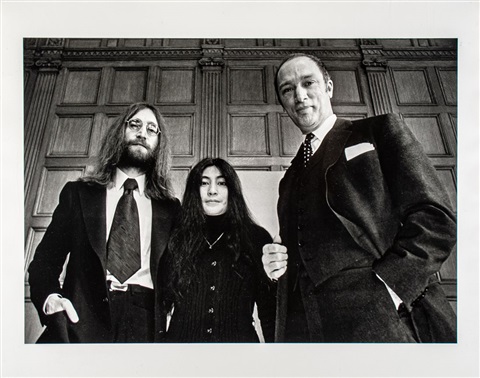

Firstly, there was the warm meeting of John and Yoko Lennon with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. I remembered that Patrick once asserted that the Beatles would have more influence on Canada than the Prime Minister of the time. And few who saw and heard it will forget the rapport of Patrick and Pierre in the telecast from CJOH-TV, Ottawa, which. entranced the Liberal delegates the night before the majority of them chose the new Prime Minister.

Secondly, on Wednesday the CRTC ruled that an old rule made by the BBG was dead. No longer is common ownership of stations in the CTV network forbidden. This removes any bar to the approval by the CRTC of the purchase by Bushnell TV (CJOH-Ottawa) of the CTV station in Montreal (Marconi’s CFCF). Patrick Watson is vice-president for programming of Bushnell TV.

Mr. Watson as author is not so clear and assured as author Trudeau, at least in prescriptions for the future, although he does present a more emotional and bitter criticism of Canadian society than the Prime Minister did in his collected essays.

The conspiracy Mr. Watson writes about “ . . . ought to be a central issue of our time.” What is it?

“. . . A conspiracy to turn us off, us people, to make us well-programmed, responsive robots. It is a conspiracy that works particularly well because the conspirators do not know there is a conspiracy and believe their actions to be good … our schools, our mass media and our politics co-operate to silence the human voice. But so successfully do they sham the opposite role that they convince themselves.”

There’s too much in the book for one day and one column. This is most apparent on the media, the field Mr. Watson knows best and where he is most interesting and suggestive. His fiercest stories and most apocalyptic views come out in his attack on the schools.

He hates the present system as much as Richard Needham does and he’s even more confident about the essential purity and worth of the child and his imagination than is the columnist. Fortunately. I think he is more optimistic about the chances of education reform.

For the past few months Mr. Watson has been carrying on an experiment in the inter-weaving of news and public affairs commentary at CJOrf. It has had some similarities to the programming CBC has been doing on Saturday and Sunday night.

The reaction among Ottawa viewers has been strong. Few seem indifferent. Both the pros and cons have been debating the merits of the Watson-Lapierre conception of TV as it ought to be.

Most reviews of Conspirators In Silence have been scathing. The reviewers seem put off by the absence of any linear development, the mixing of anecdote with lofty, potted sermons and nudging, intimate, personal convictions.

I struggled as a reader between embarrassment at the un-historical, unstructured blend of didacticism with assurance and admiration for the author’s rank confidence that he is a revolutionary with a message.

Another day I can return to Watson, the TV executive, with ideas which he believes are revolutionary. Let’s close with Watson on Trudeau. He sees the PM as John and Yoko found him last Tuesday, one of the truly beautiful people. “Custom stales. . . .” as Shakespeare wrote, and many of us in the political business are seeing the warts, perhaps too many of them, because we’re so accustomed to him now.

“Each morning, when we see his picture on the front page, and read beneath that Prime Minister Trudeau said something, visited somewhere, kissed someone, we feel uneasy; he does not wear a Prime Minister’s mask. Those who love him, or what he appears to be, mistrust their judgment sometimes. ”

Why did the Liberals choose Trudeau? “. . . the overriding reason for his election was the conviction that his popularity would keep the party in power

“He himself appeared threatening to the traditional party structures, as he was, in fact. But many of the Old Guard, knowing it had been done before, would comfort themselves with the knowledge that once they had him trapped, which is to say elected, they could serenely proceed with the business of smoothing off his corners and turning his mask into a party mask after all.

“The reason for his popularity in the country, of course, had to do with style, a style that was personal, not institutional. Governments, like advertisers, have learned to lie with such facility that they have scarified their right to the people’s faith. But the Trudeau style was believable, and to the young of mind, impatient with all the old political platitudes, it was even more important to believe him than to agree with him.

“In Trudeau, the scholar’s commitment to unqualified truth dances attendance upon a willingness to compromise, without denying that there is a difference between compromise and the ideal.

“ . . . We find him a man who has come to terms with change and who clearly sees that, in the current of human social and political events, entrenchment and rigidity of systems and institutions are likely to threaten that which really matters: The liberty and fulfilment of the individual.

Mr. Watson puzzles about what has happened to Mr. Trudeau since June. To him “he seemed unwilling to accept either the magical mantle he had been given by the country, or the electric personal connection he had forged with its people. He retreated. He refused again and again, to appear on television and keep alive the contact … the naturally fickle immediately sensed they had been wrong and chalked up another foiled love affair. The faithful sensed the rightness of their faith, but waited for a sign.

“ . . . Trudeau acts more like a teacher than any prime minister ever acted before — he has puzzled the country. … If we are uncertain about Trudeau, it has to be recalled that he himself has made uncertainty almost a principle of government. If he really means that, there is a gleam of hope because the uncertainties can be dealt with only by loosening the traditional iron grasp on power, positive or negative, and acknowledging a new kind of democratic relationship.”

Mr. Watson is much more one of “the faithful” than “naturally fickle.” He, too, seeks a new kind of democratic relationship, with a stress on participation, on youth, on a destruction of the myth that Ottawa can solve problems.