21 Dec LIFE AT THE CORE OF THE BEATLES’ APPLE

THE TYCOONS JOHN, PAUL, GEORGE, RINGO

Apple Corps! Champion of the talented underdog, anti- Kstablishment’s greatest snoot-cocker, nay-sayer to the fat cats of the music world—or so proclaimed the Beatles when they launched their much-publicized business project.

But it hasn’t quite worked out that way. The Apple’s not so rosy these days and the complaints that are increasingly being heard are all directed at a white, five- story building at No. 3, Savile Row, the London headquarters of the Beatles’ fruitful empire.

A grey Rolls-Royce purrs outside the entrance. In the back seat is Paul McCartney and his latest girlfriend, Linda Eastman, a slim blonde who once worked as a photographer in New York.

Beside the Rolls stands a uniformed chauffeur, looking like a heavy from a Matt Helm movie thriller. Behind the thick, white, wooden door of Apple, a mini- skirted girl chewing bubble-gum sits grandly at a large white table. White chairs are scattered around the room. The walls are white, too. So is the latest Beatle album cover. White is in.

People come and go at Apple, just as in any other office. But here the percentage of oddballs is considerably higher than the average.

A man in his mid-thirties wanders in, one quivering hand raised above his head like a young child in school asking to go to the washroom.

He stammers as he tells the girl he sent a letter to Mr. McCartney a few weeks back. He wonders if he could speak with Mr. McCartney about his idea. The girl politely tells him a reply is surely on its way. But he wants to know the details of the reply. Was his letter ever received by Paul? Don’t they know he can’t sit around all day waiting for Mr. McCartney?

The girl suggests the man sit down and write another note. He lowers his hand, sits down and starts writing.

While the man writes and mutters to himself, the girl winks at me. Someone else comes in and asks for an Apple executive. He is also told to wait. Waiting is the way things are done at Apple.

A middle-aged man with long sideburns glides out of the inner offices, passes a phony-sounding compliment to the girl, ‘strides out the door, into the Rolls, and kisses McCartney’s girl. The car pulls away.

The letter writer, meanwhile, has thrown away two sheets of paper and is using a third, all the while twitching. Suddenly he leaps Tap and starts wildly stroking the white seat cover. S”

“I’m a film maker,’’ he shouts, “and I’ve got dirty pants and I’m messing up your nice chairs! No, I’m a celluloid man. That’s better.” He writes a few more words. And then he jumps up again and shouts: “Why don’t they all leave me alone?”

This scene is not unique at Apple, I was told. Unbalanced people are attracted by Apple’s promise of artistic understanding and financial backing.

Terry Doran. 28, director of Apple Publishing, said when the company was formed: “Because the Beatles have made a lot of money, people expect that they’ll retire and just go off and enjoy themselves. But they are interested in creating, and they want to help people- young people with talent and ambition who find that no one wants to listen to them.”

Said John Lennon: “The aim of the company isn’t a stack of gold teeth in the bank. We’ve done that bit. It’s more of a trick to see if we can get artistic freedom within a business structure; to see if we can create things and sell them without charging three times the cost.”

Said Paul McCartney: “We want to help other people, but without doing it like charity and without seeming like patrons of the arts. We always had to go to the

big man on our knees, touch our forelocks and say. ‘Please, can we do so and so?* And most of those companies are so big, and so out of touch with people like us who just want to sing or make films, that everyone has a bad time.

“We are just trying to set up a good organization, not some great fat institution that doesn’t care. We don’t want people to say yessir, nossir. We hope that at Apple if someone can produce a record better then me they’ll say so: I’m not on some big ego trip. I mean, we re in the happy position of not needing any more money, so the first time the bosses aren’t in it for the profit. If you come to see me and say, ‘I’ve had such and such a dream,* I will say, ‘Here’s so much money. Go away and do it’.”

In short. Apple looked like Utopia for young people frustrated by the Establishment way of not getting things done. No red tape, no begging for a break. A sympathetic, turned-on ear seemed to be the system in Apple Corps.

But many people working in the London music business think Apple Corps has not lived up to its early promises. Their main complaint has to do with the claims Apple made when it was set up six months ago. Rather than becoming a benevolent uncle it appears the Apple organization has joined the Establishment: its attitude to struggling, undiscovered young* tdlent is one of indifference.

Apple is basically a holding company of publicly unknown assets, although speculation puts its original financial backing at $2.4-million. It employs about 50 people, including Ron Kass. a former overseas representative of a U.S. record company, and Alexis Mardas, a Greek who is reputed to be a budding electronics genius.

At one time it also operated at the retail level, with an Apple Boutique in Baker Street. But that closed—and about $42,000 worth of zany mod clothes was given away —when the Beatles tired of being shopkeepers.

The company is involved not only in supplying the world with new Beatles records, but in producing films, new songs—almost anything that sells. So far Apple has released four singles and one LP.

Despite Apple’s offbeat philosophy, few doubted the company would be a financial success. The Beatles’ recording and publishing royalties alone would take care of that. Hey Jude sold more than 6-million copies. The group gets 7 per cent of 90 per cent of the retail price of each copy, which amounts to about $420,000 recording royalties on that disc alone.

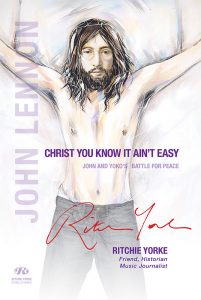

CHRIST YOU KNOW IT AIN’T EASY

JOHN AND YOKO’S BATTLE FOR PEACE

It’s common to see large groups of people waiting for hours—even days—to discuss their hopes with Apple. “I’ve been there and seen hundreds of songwriters lined up,” said Barry Gibb, a member of the Bee Gees pop group. “Whenever somebody came out, they all yelled and begged for a chance to see John or Paul. It was really a pitiful scene.”

Gibb also tells a story indicating that Apple has yet to find an effective way of dealing with the egos of young talent. “Paul wanted a song for Mary Hopkin, and he called me up. I sent him one. and he called to tell me he liked it and would use it as a flip side or on the album.

“I told him to forget it. I only write A sides now. It would be humilating to do otherwise.”

Apple is having its problems with Miss Hopkin’s career. The company has received more than 1,500 songs for her, yet an executive admitted only five had been recorded. This is less than half the number of tracks required for the album which Capitol Records, Apple’s North American distributer, has been pleading for. Miss Hopkin. meanwhile, will not talk to the press.

Apple’s main trouble, said one staff member, who didn’t wish to be identified, is disorganization. He mentioned the case of a U.S. magazine which paid $4 000 for an exclusive color shot of the Beatles for a front cover. Then an executive gave prints to other magazines.

Certainly Apple’s press relations leave much to be desired, and possibly may account for the severe criticism of the Beatles by Fleet Street recently. It is almost impossible to interview the Beatles through official channels. Approaches must be made through friends, other pop stars, or girls, and even these rarely succeed.

When I attempted to obtain an interview with John Lennon, I was asked if my newspaper would be willing to pay Lennon for it.

In London you hear many stories about people who had their hopes raised by Apple, only to be disillusioned.

One of them is Clive Williams, 30, a Toronto “management counsellor” who went to London to try to Intel , est Apple in a “really different kind of Canadian furniture enterprise.”

“The first thing 1 did on arrival at London Alt (nut was rush off to Aople, bags in hand.” he said thl* • I “It felt like walking into a sticky, glutinous hall I w • very let down.”

After several days of hanging around, Williams finally saw Derek Taylor, Apple publicist. One of l a\ lor’s remarks to Williams was, “OK, man, but what will all this do for the revolution?” That apparently wh* the climax of Williams’ 4,000-mile trip.

Taylor also reportedly told Williams that Apple has no money.

“1 was sucked in by the promises of Apple being a trading post for venturesome young people who were hamstrung by the Establishment. I spent $500 trying to get Apple’s aid and all I got was abuse.

“It’s an incredibly bad scene. Apple employees don’t want to see anybody, and they do their best to put you down. Taylor was surrounded by a bunch df yes boys, who kept agreeing with everything he said.”

One unhappy employee said the Beatles should hire an experienced businessman to reorganize Apple—grey suit and white . shirt or not. McCartney seems to be aware of this. He tried to interest Lord Beeching former deputy chairman of Imperial Chemical Industries and the man who modernized the British railway system, in taking over Apple.

“I’d like to help the Beatles, as I greatly admire their talent, but it is not an appointment to which I could give total involvement as I see it now,” Lord Beeching said.

One disillusioned Apple consultant said he was disgusted by the lack of sincerity among other employees, though not necessarily the Beatles themselves.

He even suggested that unless there is a radical change in the way things are running at Apple, the Corps might well turn into a corpse.